Global public debt is very high. It is expected to exceed $100 trillion, or about 93 percent of global gross domestic product by the end of this year and will approach 100 percent of GDP by 2030. This is 10 percentage points of GDP above 2019, that is, before the pandemic.

While the picture is not homogeneous—public debt is expected to stabilize or decline for two thirds of countries—the October 2024 Fiscal Monitor shows that future debt levels could be even higher than projected, and much larger fiscal adjustments than currently projected are required to stabilize or reduce it with a high probability. The report argues that countries should confront debt risks now with carefully designed fiscal policies that protect growth and vulnerable households, while taking advantage of the monetary policy easing cycle.

Worse than expected

The fiscal outlook of many countries might be worse than expected for three reasons: large spending pressures, optimism bias of debt projections, and sizable unidentified debt.

Previous IMF research has shown that fiscal discourse across the political spectrum has increasingly tilted toward higher spending. And countries will need to increasingly spend more to cope with aging and healthcare; with the green transition and climate adaptation; and with defense and energy security, due to growing geopolitical tensions.

On the other side, past experience suggests that debt projections tend to underestimate actual outcomes by a sizable margin. Realized debt-to-GDP ratios five-years ahead can be 10 percentage points of GDP higher than projected on average.

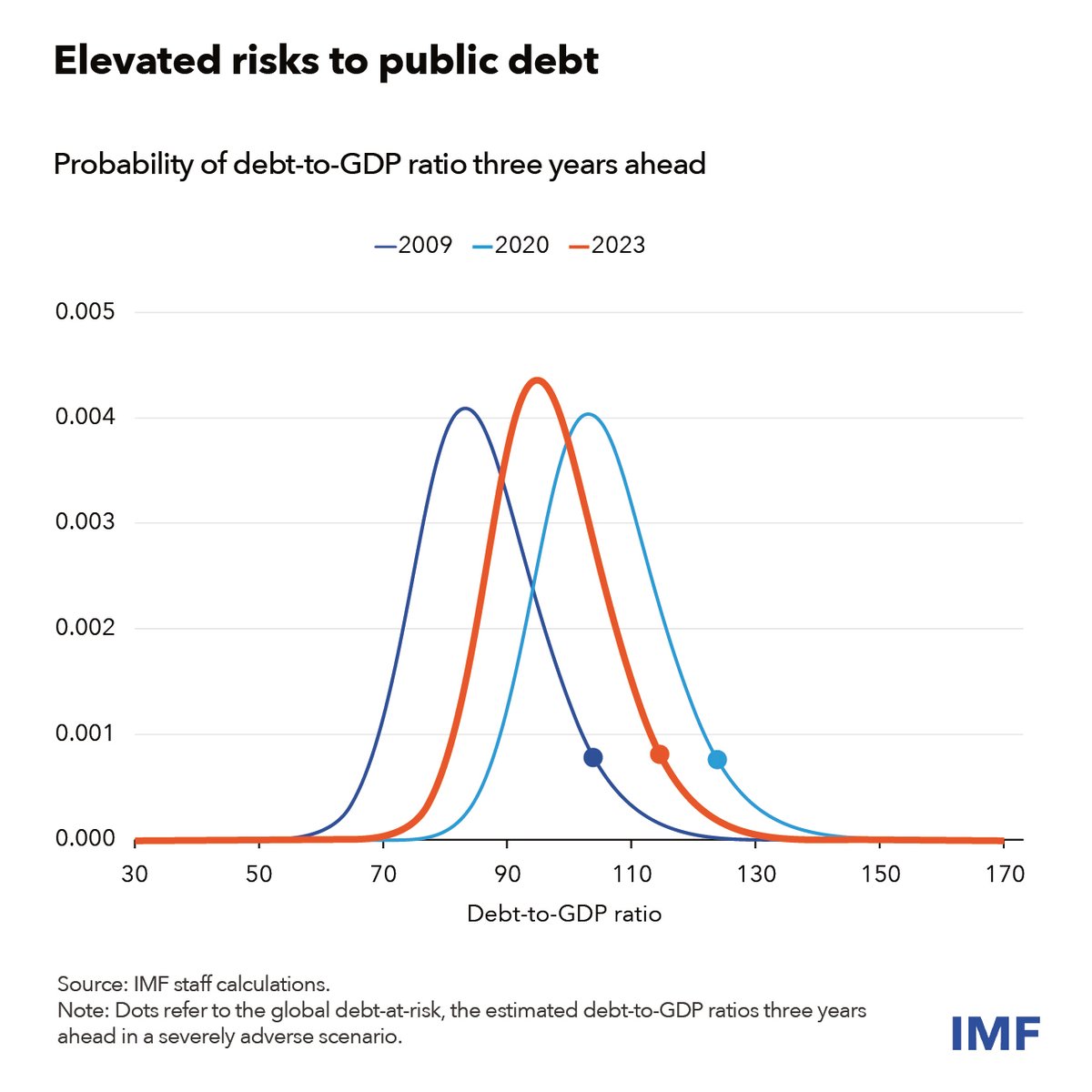

The Fiscal Monitor presents a novel “debt-at-risk” framework linking current macro-financial and political conditions to the entire spectrum of possible future debt outcomes. This approach goes beyond the typical focus on the point estimates of debt forecasts and helps policymakers quantify risks to the debt outlook and identify their sources.

This framework shows that in a severely adverse scenario global public debt could reach 115 percent of GDP in three years—nearly 20 percentage points higher than currently projected. This could be due to several reasons: weaker growth, tighter financing conditions, fiscal slippages, and greater economic and policy uncertainty. Importantly, countries are increasingly vulnerable to global factors affecting their borrowing costs, including spillovers from greater policy uncertainty in systematically important countries, such as the United States.

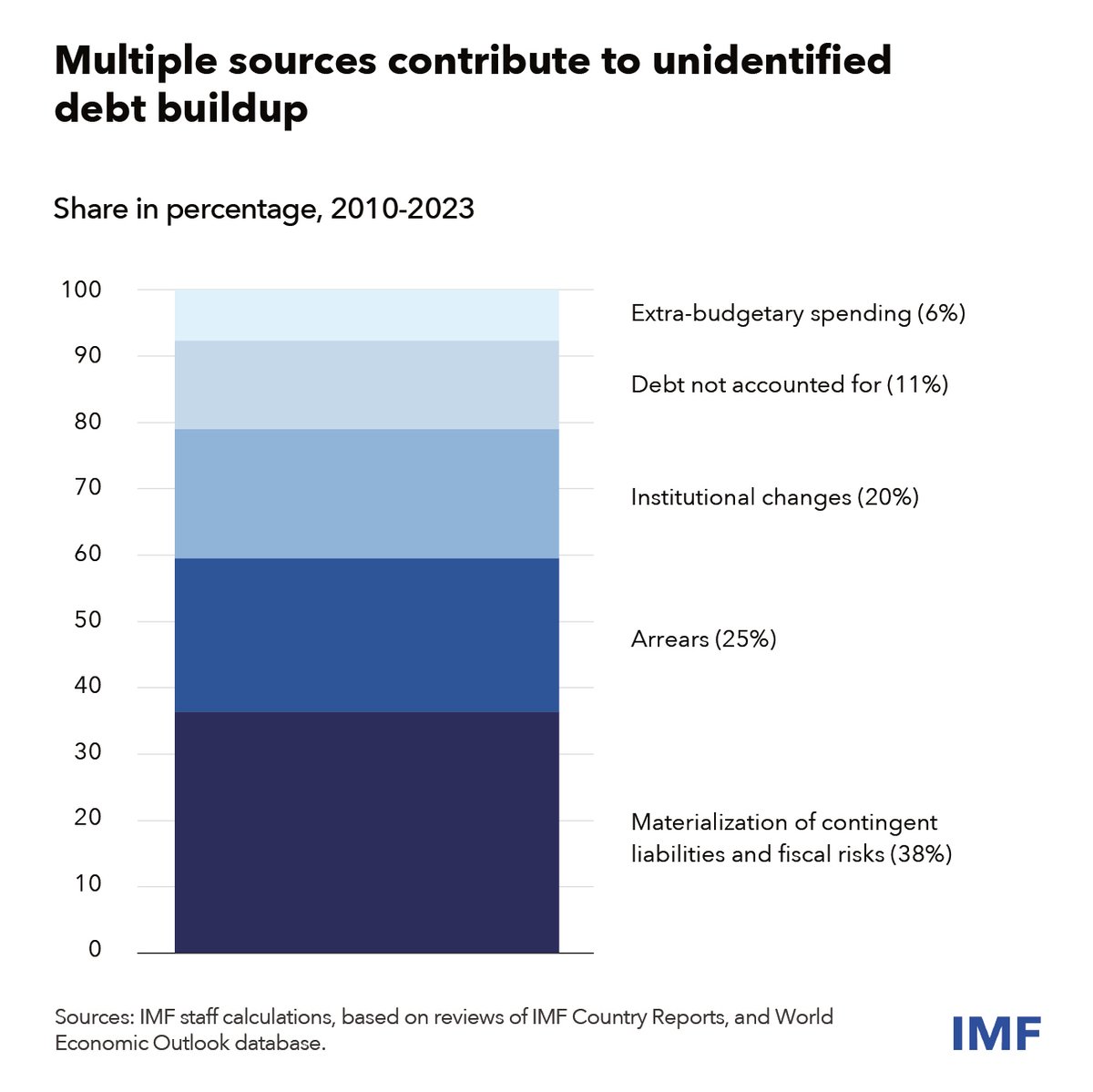

Sizable unidentified debt is another reason for public debt to end up being significantly higher than projected. An analysis of more than 30 countries finds that 40 percent of unidentified debt stems from contingent liabilities and fiscal risks governments face, of which most are related to losses in state-owned enterprises. Historically, unidentified debt has been large, ranging from 1 to 1.5 percent of GDP on average, and it increases sharply during periods of financial stress.

Larger fiscal consolidation

If public debt is higher than it looks, current fiscal efforts are likely smaller than needed.

Fiscal adjustment plays a crucial role in containing debt risks. With inflation moderating and central banks lowering policy rates, economies are better positioned now to absorb the economic effects of fiscal tightening. Delaying would be both costly and risky, as the required correction grows as time goes by; and experience shows that high debt and lack of credible fiscal plans can trigger adverse market reaction, constraining room to maneuver in the face of turbulence.

Our analysis, accounting for country-specific risks surrounding the debt outlook, suggests that current fiscal adjustments—on average, of 1 percent of GDP over six years by 2029—even if implemented in full, are not enough to significantly reduce or stabilize debt with a high probability. A cumulative tightening of about 3.8 percent of GDP over the same period would be needed for an average economy to ensure a high likelihood of debt stabilization. In countries where debt is not projected to stabilize, such as China and the United States, the required effort is substantially greater. But these two largest economies have a much richer set of policy choices than other countries.

Focus on people

Such large fiscal adjustments, if not well calibrated, will entail large output losses as aggregate demand falls and can harm vulnerable groups and lead to higher inequality. A careful design is thus needed to mitigate the costs of the adjustment and to garner public support for needed fiscal adjustment.

The choice of fiscal measures matters because the impacts are not alike and involve trade-offs. For example, cuts in public investment have the largest output losses and hurt long-term growth prospects, while reducing social transfers hurts vulnerable households and raises inequality.

A judicious mix of people- and growth-focused fiscal measures is needed and will vary across countries. Advanced economies should advance entitlement reforms, reprioritize expenditures, and increase revenues where taxation is low. Emerging market and developing economies have greater potential to mobilize tax revenues—by broadening tax bases and enhancing revenue administration capacity—while strengthening social safety nets and safeguarding public investment to support long-term growth.

Speed also matters. Our analysis suggests that a measured and sustained pace of adjustment would alleviate fiscal risks, while limiting the negative impact on output and inequality by about 40 percent less than a more abrupt tightening. That said, some countries with high risk of debt distress will need front-loaded adjustments.

Adjustments need to be accompanied by stronger fiscal governance, including credible medium-term frameworks, independent fiscal councils, and sound risk management. Enhancing fiscal risk assessment, monitoring closely contingent liabilities in state-owned enterprises, and publishing granular and timely debt statistics can reduce unidentified debt.

High public debt is a concern. Even for some countries where the public debt levels seem manageable, the Fiscal Monitor argues that risks are elevated, and actual debt outcomes in coming years may be worse than projected. Current adjustment plans are not enough to stabilize or reduce debt confidently. The report also shows that well-designed fiscal adjustments can help reduce debt risks, improve public debt outlooks, and mitigate the adverse impact on society.